AN EXERCISE IN ALLEGORY: A Critical Analysis and Interpretation of Allegorical Subtext in Modern Day Fantasies

A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Film and Television Department in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the

Degree of Master of Fine Arts Savannah College of Art and Design

By Michael Moore Pearce Jr.

Thesis Abstract

This thesis hypothesizes that modern film audiences are far more susceptible to internalize morality tales and socially aware cinema when the ideological messages are masked in the guise of fantasy, science fiction, and satire. Within the course of this paper, I will analyze five films that have approached a certain thematic topic through allegory. The success of these films will be evaluated according to the film's financial success (domestic and international box office grosses) and critical reception. The paper will then compare the film with other pictures that explored similar thematic material but approached the topic in a straightforward, "unveiled" manner. The remainder of this paper will deconstruct this hypothesis and analyze how this premise has served as a primary guiding principle for my MFA Graduate Thesis film at Savannah College of Art and Design. The film's title is Paradise.

Introduction: Allegory and Audience

In a conversation with Jack Nicholson on the set of The Shining Stanley Kubrick stated that in filmmaking "You never try to photograph the reality of the situation, you try and photograph the photograph of the reality." (Kubrick 2001) Kubrick was stating that within a scene, you never play "reality for the sake of reality." (Kubrick 2001) "Yeah" he would quickly retort, "It's real but it's not interesting." (Kubrick 2001) Kubrick believed that filmmakers must slightly skew reality a few degrees for an audience to be able to accept a scene. In very "un-Kubrick" fashion, the director was elaborating on his method of exploring subject matter and themes within his films. I believe Kubrick's statement extends not just to his own process as a director, but also broadly comments on the relationship between a film and its audience.

It is my belief that audiences are far more susceptible to internalize morality tales and socially aware cinema when the ideological messages are masked in the guise of fantasy, science fiction, and satire. Within the course of this paper, I will analyze five films that have approached a certain thematic topic through allegory. The success of these films will be evaluated according to the film's financial success (domestic and international box office grosses) and critical reception. I will then compare it with other films that explored similar thematic material but approached the topic in a straightforward, "unveiled" manner. Within the selection of films, audiences are receiving the same central thematic message. However, in one film the message is told in a fantastic setting, detached from reality. The comparable film is set in a realistic setting. The remainder of this paper will deconstruct this hypothesis and analyze how this premise has served as a primary guiding principle for my MFA Graduate Thesis film at Savannah College of Art and Design. The film's title is Paradise.

While my thesis film Paradise may be told under the guise of fantasy, the relationships within the film, the thematic material, and the conflicts explored are deeply routed in a living, tangible reality. Fantasies and science fiction stories, tales which often take place in different worlds and far away galaxies, have always been used as a tool to explore extremely intimate, personal stories and controversial subject matter. In a 1967 interview with Playboy magazine promoting 2001: A Space Odyssey, Stanley Kubrick stated "You don't find reality in your backyard. In fact, sometimes that's the last place you'll find it." (Ciment 2003) From classical literature such as Homer's The Illiad and Grimm's Fairy Tales, to Tolkien's Lord of the Rings and Neil Blomkamp's modern science fiction film District 9, storytellers have always employed fantasy, science fiction, and satire to mask much deeper, controversial subject matter that may not be as effectively told if presented in a straightforward dramatic piece.

Paradise is set in the 1600's and features two men who venture deep into the unspoiled American wilderness to search out the mythical fountain of youth, with hopes of saving the dying colony. However, once they discover the magical body of water, they find themselves unwilling to leave it, afraid that the water's power will fail unless they stay close. The two find themselves paralyzed by fear and unwilling to part. Burdened by feelings of guilt and a depreciating bond, they slowly turn on each other.

Paradise is told within a fantastical setting because fantasies offer a powerful medium to portray modern day morality tales. Fantasies offer a reflection of our own reality. "However circumscribed their (fantasies) scope or clichéd their language, fantasies are meaningful in how they embody the difficulties, limits, and struggles of human understanding." (Brottman 2003) Audiences are able to accept and learn from characters and events more easily when told within some form of exaggerated reality or fantasy, rather than when the story is presented as a traditional, straightforward drama. This is due to the detachment of reality. In fantasies and works of science fiction, the worlds our characters inhabit are not our own. Audiences look upon these new and unexplored settings with pure eyes, unhampered by their own preconceived notions and rationalizations.

An Alternative Approach

"Fantasies are driven by the narrative powers of allegory and enigma, and by the tantalizing hope that life-illuminating wisdom lies couched in cryptic lore." (Brottman 2003) This quote is in reference to a literary critic's deconstruction of J.R.R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings. The implications of this passage are just as applicable to cinema as it is to literature. In this instance "cryptic lore" includes all of the genre conventions of fantasy filmmaking: space ships, aliens, swords and sandals, wizards, etc. "Life illuminating wisdom" refers to the central themes and morals of the story. The author clearly supports the notion that fantasy acts as a conduit of information that may be overlooked or unaccepted in dramatic pieces.

This philosophy of storytelling has been explored and expanded in modern filmmaking. In Dr. Strangelove, Kubrick examines cold war fears through an exaggerated, satiric hyper reality. District 9 explores apartheid and racism through the use of an alien occupancy. The Dark Knight offers cinema's most effective comment on America's post 9/11 paranoia and military occupancy. Avatar reinvents the European imperialist invasion of the Native Americans, and Pan's Labyrinth is an examination of Spain under fascist rule.

These films are all genre pictures that excel at utilizing subtext to tell their stories; stories that are meant to offer audiences a reflection through which they can judge and evaluate their own lives.

The Dark Knight: The Seminal Post-9/11 Film

Christopher Nolan's seminal superhero film The Dark Knight opened on July 18th, 2008 and made $158,451,483. The film was a critical and box office sensation. It earned a total domestic box office gross of $533,345,358 and a worldwide box office gross of $1,001,921,825. (Box Office Mojo) At the end of its theatrical run, The Dark Knight was second only to Titanic in the history of box office gross. Not only was the film a money making juggernaut but the movie was universally praised by film critics, earning a 94% rating on Rotten Tomatoes (an esteemed online movie review aggregator), eight Oscar nominations, and two Oscar wins.

While many audience members were no doubt brought to the theater merely to see the iconographic character battle evil and save the girl, The Dark Knight, as recognized by critics, is truly a testament of the times. The film may also be the most successful motion picture that depicted the growing paranoia and civil unease that gripped an American society still recovering from the September 11th terrorist attacks. Other films produced during this period addressed these same issues, for "Art always reflects society, intentionally or not." (Alworth 2008)

In reference to the films released during this time, film critic Jeff Alworth stated: "In the past few years, we've seen a number of documentaries about the war on terror and Iraq, and even a couple movies that overtly addressed it. But sometimes, it's the movies that don't intend to directly comment on these themes that offer the sharpest critiques." (Alworth 2008) Another review goes on to state "Curiously, it has been the fantasy film, The Dark Knight, that has offered its fans a perspective on the war effort that the anti-war films of the past two years have failed to provide." (Orenstein 2008)

Many of these other films dealing with a post 9/11 America failed at the box office and were received with lukewarm reviews from the critical community. This suggests "The Dark Knight’s popularity may also reflect a collective discomfort and ambiguity regarding the Bush administration’s response to 9/11 by declaring a war on terror and turning to the dark side of torture and rendition." (Briley 2008) This is my central point; audiences respond to socially relevant and morally ambiguous films. However, they do not want their messages to be too overt or too aggressive.

Let us analyze a single moment from the film. In an interrogation scene, which is the first time that Batman and The Joker have a conversation, much of the Joker's moral philosophies are illuminated. Bale demands to know "Where's Dent?" Ledger quips, "You have all of these rules and you think that they will save you." This is met with a massive blow from Bale, responding to the Jokers lack of cooperation and escalating the violence within the scene, before demanding once again, "Where's Dent?" Ledger responds to this heightened intensity, but adversely to what Bale is hoping. He appears to be taking satisfaction in this escalation. Ledger goes on to state "The only sensible way to live in this world is without

rules." This is a comment on Bale's own moral belief that there are lines not to be crossed in an interrogation.

Bale then delivers his most vicious blow, knocking the Joker back as he cackles in delight. The ultimate mix of pleasure and insanity overtakes Ledger's face as he states, "You have nothing... nothing to threaten me with. Nothing to do with all of your strength." This comment represents one of the central questions the film raises the question: How do we fight an enemy that operates outside of our understanding and an enemy we cannot appease; an enemy that merely wants to "Watch the world burn"? Within this scene and the larger picture, the Joker's motives seem to be strikingly similar to the American population's understanding of modern day extremists and "terrorists".

A close reading of this scene suggests much of the same thematic material being explored in other films during this time period. In the Valley of Ellah (Paul Haggis), Redacted (Brian DePalma), Rendition (Gavin Hood), Lions for Lambs (Robert Redford), and The Green Zone (Paul Greengrass) all dealt with how we as humans reconcile the horrors and moral ambiguities of the current "war on terror". These films were made with world-class directors and first-rate casts, and yet all of them underperformed at the box office. In fact, the only other film during this time period that could be considered a financial success, and a minimal one at that, would be Peter Berg's The Kingdom. It could also be argued that it was successful for many of the same reasons that The Dark Knight was successful; it is first and foremost an entertaining picture that thinly veils its ideological philosophies.

In summation, I fully believe that if The Dark Knight not been filled with such overt social and cultural allegories, it still would have made money. However, audiences can and will respond to challenging messages within films when those messages are presented to them in the correct manner, and it is these challenging notions that caused The Dark Knight to rise from blockbuster status and into a cultural phenomenon.

Dr. Strangelove: How Audiences Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb

Stanley Kubrick's Dr. Strangelove is a satiric comedy and not a fantasy. However, many of the same elements that make fantasies such a strong mode of conveying veiled ideological messages remain true for satiric comedy.

Following the critical and box office success of his controversial film Lolita Stanley Kubrick turned his attention to developing his next project. Kubrick started with nothing but a "vague idea to make a thriller about a nuclear accident, building on the widespread Cold War fear for survival." (Siano 1995) Kubrick came across Peter George's novel Red Alert and bought the film rights to the book. However, the story was an over-wrought melodrama and Kubrick had a difficult time adapting the piece into a viable film that could stand on its own merit, while maintaining the novel's central themes.

In an interview Kubrick commented that: "as I tried to build the detail for a scene I found myself tossing away what seemed to me to be very truthful insights because I was afraid the audience would laugh. After a few weeks of this I realized that these incongruous bits of reality were closer to the truth than anything else I was able to imagine. After all, what could be more absurd than the very idea of two mega-powers willing to wipe out all human life because of an accident, spiced up by political differences that will seem as meaningless to people a hundred years from now as the theological conflicts of the Middle Ages appear to us today?" (Siano 1995)

From this point on Kubrick opted that the film needed to be told "as a nightmare comedy." (Siano 1995) Kubrick went on to say, "following this approach, I found it never interfered with presenting well-reasoned arguments. In culling the incongruous, it seemed to me to be less stylized and more realistic than any so-called serious, realistic treatment, which in fact is more stylized than life itself by its careful exclusion of the banal, the absurd, and the incongruous. In the context of impending world destruction, hypocrisy, misunderstanding, lechery, paranoia, ambition, euphemism, patriotism, heroism, and even reasonableness can evoke a grisly laugh." (Siano 1995)

Audiences unanimously agreed with Kubrick and the course he took. The film cost only $1.8 million to produce and earned $9,440,272 domestically. (Box Office Mojo) The critical community adored the film. The film has a 100% rating on Rotten Tomatoes. It was nominated for four academy awards and has been hailed by Robert Ebert as "arguably the best political satire of the century." (Ebert 1999)

Other films during this time were being produced with the same subject matter. Sidney Lumet produced a straightforward adaptation of Peter George's Red Alert at the same time as Kubrick was filming Dr. Strangelove. The film was titled Fail-Safe and starred the immensely popular Henry Fonda as the American President and Walter Matthau as the advisor to the Pentagon. The film arrived in theaters seven months after Dr. Strangelove and while the film received critical praise (a 94% rating on Rotten Tomatoes) it failed at the box office. Fail-Safe simply didn't resonate with audiences in the same way as Dr. Strangelove.

Red Alert told almost precisely the same story as Dr. Strangelove. However, Kubrick employed a fantastic setting, filled with exaggerated characterizations, oblique sexual references, and potty humor. Fail Safe told a bleak, somber cautionary tale. The film strives to provide the utmost realism. One method of telling this identical story proved infinitely more successful than the other. We are to learn from this examination that the message of a film alone will not bring an audience to the theaters. It is the manner in which that message is told. The "dramatic irony approach is probably the only way Dr. Strangelove could have been successful. Only through the natural distancing that comedy provides could it have been possible to make a film at the height of the Cold War that essentially posits the notion that neither America nor the Soviet Union could make a claim to the high moral ground as long as both were building atomic bombs." (Sexton 2006)

The differences between the two films are stark. In both films there is a scene where the two presidents and their chief advisors speak of the consequences of a nuclear strike and the possibility of complete annihilation. In Dr. Strangelove, George S. Scott's discusses the potential positives of a nuclear war. Scott truly appears to be in a boy's tree house rather than the "War Room". He loudly chews bubble gum as he proudly declares he can safely exterminate the Russian population. He is constantly moving within the room, visibly showing his enthusiasm for the games being played within the setting. And when the President of the United States calls him down, Scott juts his bottom lip out like a child scolded for getting his clothes dirty, before sitting down to sulk.

In Fail-Safe, Henry Fonda delivers a pained, dramatic speech. There is no music. There is only the quiet and Fonda's philosophical notions of right and wrong. He gives a soliloquy that would seem at home in a Shakespeare play. "We're to blame, both of us, we let our machines get in the way." "If we are men, we must say that this will not happen again. Is it possible?" There is a weight to this film, within this scene particularly, where the focus is on the individual rather than the faceless whole, which is the audience that George C. Scott feels more comfortable recognizing.

In this scene, Lumet is clearly stating his own ideological message. Kubrick's was far more veiled. "Ultimately the most critical decision he made in approaching the subject of nuclear destruction came from his perceiving how comedy can infiltrate the mind's defense mechanism and take it by surprise." (Ebert 1999) The audience received the message, but not because it was explicitly stated. The audience received the message because it is ever-present in the lunacy of the entire film. This is the genius of Kubrick and the primary reason why Dr. Strangelove succeeded at finding an audience and articulating its message when Fail Safe failed. "Despite the fact that the nightmarish possibilities of the Cold War become haunting and real as the movie climaxes, the film manages to maintain a level of silliness that emotionally distances the viewer from the horrors to a comfortable level, allowing for an analysis of the lighter and more important themes within. " (Ebert 1999)

District 9: Exploring Apartheid in Summer Sci-Fi

With the release of films such as Star Trek, Transformers 2: Revenge of the Fallen, and Up, the 2009 summer movie season broke all records and financial expectations. However, just as summer was beginning to fade movie audiences were introduced to Neil Blomkamp, a first time feature director and protégé of Peter Jackson and Fran Walsh. With a budget of approximately $30 million dollars (Transformers 2 cost $200 million) Blomkamp produced District 9. The film was an immensely successful science fiction cautionary tale, complete with the special effects and action sequences that summer audiences have become accustomed to, but at only a fraction of the cost. The film went on to gross $204,838,037 worldwide. (Box Office Mojo) District 9 was also met with surprising praise from critics, especially for a late summer Sci-Fi opening. The picture earned a 90% rating at Rotten Tomatoes and was nominated for four Oscars.

District 9's synopsis is as follows: "In 1982, a massive star ship bearing a bedraggled alien population, nicknamed "The Prawns," appeared over Johannesburg, South Africa. Twenty-eight years later, the initial welcome by the human population has faded. The refugee camp where the aliens were located has deteriorated into a militarized ghetto called District 9, where they are confined and exploited in squalor. In 2010, the munitions corporation, Multi-National United, is contracted to forcibly evict the population." (IMDB.com)

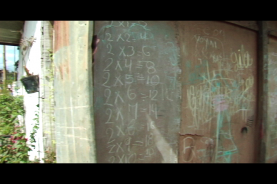

Upon release of the film obvious comparisons were drawn to South Africa's segregationist history. Blomkamp, a native of Johannesberg stated, "The whole film exists because of that. I was trying to make the science fiction feel vaguely familiar.” (Itzkoff 2009) Mr. Blomkamp went on to say, “The South African component would be the alien component.” (Itzkoff 2009) The plight of the film’s crustacean-like extraterrestrials can be interpreted as a metaphor for the persecution of South African blacks under apartheid. Mr. Blomkamp said he was also "trying to comment on how the country’s impoverished peoples oppress one another. While “District 9” was being filmed in the Chiawelo section of Soweto, Alexandra and other townships were ravaged by outbursts of xenophobic violence perpetrated by indigenous South Africans upon illegal immigrants from Zimbabwe, Malawi and elsewhere." (Itzkoff 2009)

Other films have explored apartheid in South Africa. Just three years before Blood Diamond, a Warner Brothers film starring Leonardo DiCaprio, Djimon Hounsou, and Jennifer Connelly, and directed by Edward Zwick (Glory, The Last Samurai) was released in the awards season of 2006. The film earned positive reviews and four Oscar nominations, but the movie lost a tremendous amount of money. Production costs neared $100 million while the film earned only $57 million. (Box Office Mojo)

The question must be asked, why did District 9 succeed while Blood Diamond failed. District 9 was without any recognizable stars, a first time director, and it was not directly related to any other franchise or film. The only name of recognition connected to the film was Sir Peter Jackson serving as the film's producer. Blood Diamond stars the lead actor in the most successful film of all time, and was directed by Oscar winner Edward Zwick, a director who specializes in grand epics with social and cultural themes. Both films explore the horrors of apartheid in South Africa and both stories are filled with action and adventure stories. However, District 9 was significantly more successful with critics and audiences alike.

District 9 was more successful because, like The Dark Knight and Dr. Strangelove, the film approached its disturbing subject matter in an oblique way. Blood Diamond was clearly set within South Africa during the apartheid. The horrors of the war are displayed on the screen in unflinching detail. Humans are photographed exacting the most heinous acts of violence on each other. However, in District 9 the conflict is not between man and man, but rather between man and alien. The conflicts and motivations between these two groups are exactly the same, the rights of one group are being manipulated and ignored by another group; however audiences had an easier time with the violence in District 9.

The same violent atrocities occur in District 9 that take place in Blood Diamond. “The movie was trying to say something about one oppressed group turning around and oppressing another." (Due 2009) Arms are frequently taken and rights are just as infringed within the ghetto settings of both films. However, audiences were far more attracted to District 9 despite the fact that audience members had a stronger relationship with the filmmakers and cast members of Blood Diamond.

The obvious explanation for this is that the mode for how these two stories were delivered, two films with the same relative subject matter, had a dramatic effect on the financial and critical success of the film. Blomkamp's allegorical exploration of apartheid was far more successful than Zwick's reality-based portrayal. The "south African setting hones the allegory of “District 9” to a sharp topical point. That country’s history of apartheid and its continuing social problems are never mentioned, but they hardly need to be." (Scott 2009) And it is in this veiling of themes, and this act of presenting disturbing material to audiences in a fractured way, that caused District 9 to be successful. Revered NY Times columnist A.O. Scott said it best: "Not that the metaphorical resonances of “District 9” aren’t rich and thought provoking. But the filmmakers don’t draw them out with a heavy, didactic hand. Instead, in the best B-movie tradition, they embed their ideas in an ingenious, propulsive and suspenseful genre entertainment, one that respects your intelligence even as it makes your eyes pop (and, once in a while, your stomach turn)." (Scott 2009)

Avatar: Revolutionizing Technology While Telling a Classic Story

After 15 years of development, James Cameron released his science fiction extravaganza Avatar to the public on December 10, 2009. The film featured state of the art 3D technology, introducing the film going public to an immersive experience that had never before been realized. The film went on to become the highest grossing movie of all time, surpassing Cameron's own Titanic, which earned $1,843,201,268 internationally. (Box Office Mojo) At the time of this writing Avatar has grossed $2,718,483,000 theatrically worldwide . The film is also planned to be re-released in August of 2010. On top of being an unprecedented commercial success, the film was praised by critics as well, earning an 82% rating on Rotten Tomatoes. Richard Corliss of Time Magazine stated, "It (Avatar) extends the possibilities of what movies can do. Cameron's talent may just be as big as his dreams." (Corlis 2009)

"Avatar is the story of an ex-Marine who finds himself thrust into hostilities on an alien planet filled with exotic life forms. As an Avatar, a human mind in an alien body, he finds himself torn between two worlds, in a desperate fight for his own survival and that of the indigenous people." (IMDB.com) Avatar, in much the same vein as Nolan's The Dark Knight and Blomkamp's District 9, employs an allegorical approach to storytelling. However, whereas The Dark Knight was exploring themes relative to the moment, the allegories within Avatar were purported to comment on both the European invasion of the Americas, and the American occupation of Iraq. Cameron has gone on record stating that both of these connections were firmly engrained in his mind as he produced the film. (Rollo 2010)

In The New American's initial review of the film the reviewer states, "Avatar, is a visually stunning epic that is a perfect allegory for any of a dozen or more Indian wars in American history." (Eddlem 2009) He went on to say that "the use of Avatars in the attack on the Na'vi also makes a perfect allegory to the Indian wars of America's settlement. Many times the colonists sought the aid of native tribes in order to subdue other more assertive tribes, and the Avatars could be compared to the tribes friendly to the colonists, who were later disposed of in subsequent wars. Divide and conquer was the strategy in the displacement of native Americans, but on Pandora the biological links between the natives makes the issue much more difficult." (Eddlem 2009)

Perhaps more so than any other movie discussed thus far, Avatar's politics and allegorical message are widely identifiable. However, while the film probably would have been a financial success despite its allegorical message I believe the basis of story is what brought audience members who might have seen the film only once back to the theater multiple times. Any film can have a big opening weekend. However it's the repeat business that transforms an average successful Hollywood blockbuster into the financial fortune that Avatar was. The film connected with audiences on a primitive level; it told them a story that they had grown up with, a story they knew very well. And yet the story was repackaged and told in a new and exciting manner.

Other films about the relationship between European imperialism and Native Americans have been released in recent years, most notably Terrence Malick's exceptionally beautiful The New World (2005). The New World essentially tells the same story as Avatar. It recounts the story of a fallen soldier and his growing relationship with the daughter of a native tribe and his eventual acceptance into this new way of life. The film received positive reviews from the critical community and was nominated for an Oscar. The New World cost only $30 million to produce, a relatively small sum considering the talent involved in the project, but it went on to gross only $12,712,093. (Box Office Mojo) And while The New World was never meant to be the box office success that Avatar was, there is a fundamental reason why audiences connected with Avatar in the way that they did while The New World remained relatively unseen.

Audiences have not always ignored historically accurate depictions of the clash between the early American colonies and Native Americans. Dances With Wolves tells a very similar story as both Avatar and The New World, and it grossed $424,208,848 internationally on a $22 million dollar budget. However, the film going public has changed significantly since the 1990's.

The public consciousness is different. There has been a definite shift in the last decade with the rise of the blockbuster and the spiraling costs to make films that are sure to perform well at the box office. This definite and well-documented shift has led to less challenging movies being produced. However, it has had at least one positive effect. More talented filmmakers such as Christopher Nolan, Peter Jackson, Martin Scorsese, Jon Favreau, and Neil Blomkamp are taking the opportunity direct higher profile blockbuster pictures, because oftentimes they cannot secure financing for smaller, more independent-minded films.

All of these filmmakers started their careers in the independent world, and have moved into mainstream blockbusters. However, these filmmakers are still telling the stories that they want to tell, and they are offering the same commentary they would otherwise have pursued. However, they must present their messages in discreet ways, satisfying the average moviegoer while at the same time presenting significantly more challenging material than the blockbusters of the eighties and nineties.

Modern day filmmakers have embraced allegory to share the stories that they need to tell. The successes of Avatar, District 9, and The Dark Knight are all examples of this. These are films that are finding their way into the public consciousness for the same reasons that The Exorcist, The Godfather, and Easy Rider resonated with audiences in the 1960's. However, due to the shifting film going landscape, they have to find different avenues to tell stories that are personal and yet financially viable. Avatar is a perfect example of this. For, "like any good allegory, the movie makes its point by exaggerating reality; there is little doubt who the "bad-guys" are and why. But also like good allegory, the point made is unquestionably valid; its aim is to get people to reexamine their presuppositions and hopefully to move them to think instead of blindly following corporate warmongers over the precipice." (Regl 2009)

Pan's Labyrinth: Exploring Identity Within Fantasy

In 2006 movie-going audiences witnessed Guillermo Del Toro (a director known primarily to American filmgoers for super-hero pictures such as Blade 2 and the Hellboy franchise) evolve from a B-movie science fiction director into an Oscar nominated auteur. Pan's Labyrinth resonated deeply with American and international audiences, bringing in $83,258,226 worldwide on a $19 million dollar budget. (Box Office Mojo) The film was also a critical success. It was nominated for six Oscars (it won three including Art Direction, Make Up, and Cinematography), earned a 95% rating on Rotten Tomatoes, and received praise such as: "A film of breathtaking visual splendor, watching Pan's Labyrinth reaffirms our sense in the possibilities of film as a medium, the wonder of a darkly beautiful fantasy that's vividly realized." (Levy 2006)

The film's synopsis is as follows: "In 1944 fascist Spain, a girl, fascinated with fairy-tales is sent along with her pregnant mother to live with her new stepfather, a ruthless captain of the Spanish army. During the night, she meets a fairy who takes her to an old faun in the center of the labyrinth. He tells her she's a princess, but must prove her royalty by surviving three gruesome tasks. If she fails, she will never prove herself to be the the true princess and will never see her real father, the king, again." (IMDB.com)

Drawing upon fairy tale classics such as Alice in Wonderland, Peter Pan, and Grimm's Fairy Tales, Del Toro deftly deconstructs the fantastic stories his audience has grown up with. He manipulates these classics and molds them to tell his own cultural history. Del Toro's decision to apply the conventions of fantasy to real life events led this film to become the sensation it was.

Pan's Labyrinth stands apart from other films discussed within the course of this study. In The Dark Knight, District 9, and Avatar the subject explored was completely separate from the film. There was no direct reference to 9/11 within The Dark Knight. Nowhere in Avatar were the Native Americans mentioned and the word "apartheid" was never uttered in District 9. The genius of Pan's Labyrinth is that our protagonist physically lives in both worlds. We as an audience view both realities and recognize the immediate relationships and foils between the two. "Both the narrative strands are equally real, equally plausible. There's no attempt to rationalize Ofelia's parallel universe by suggesting it's a dream or a fantasy. In fact the two sides of the film come together to constitute an allegory about the soul and the national identity of Spain, and in a wider sense about the struggle between good and evil, between the humane and the inhumane, the civilized and the barbaric." (French 2006)

There are no notable films to which Pan's Labyrinth can be compared. It is entirely original in its premise and its blending of the real and the fantastic. This is the magic of what Del Toro has accomplished with his film. In all of Del Toro's films, there is "no clear demarcation between reality and fantasy, since the former tends to be sensualist and surreal, and the latter both realistic and gaudy. Pans Labyrinth blends a number of seemingly contradictory concepts to an advantage. The film is a genre and a personal-auteurist statement. Its both gothic, horror, and fantasy. Its historically specific and politically grounded but also universal in its cinematic and mythic properties." (Levy 2006)

Pan's Labyrinth resonated with audiences for many of the same reasons that Avatar did. It was an entirely original visual experience. However, at the same time it presented us with thematic material that resonated deep within the public consciousness. It was new and yet it was instantly relatable. The fact that Del Toro was directly referencing the Spanish Revolution and embracing his own cultural heritage doesn't matter. The mythology and the deep psychological underpinnings that Del Toro was embracing and making his own is what audiences connected to. The motifs are universal to all moviegoers; the film resonates because it touches upon deep archetypes that are inherent within. And it embraces fantasy as the means to build that connection with his audience.

"Our language is rooted in the idea that the visible world is not all there is (think of a concept like inner beauty), and that to understand the world fully we must allow our imaginations to stretch beyond the things we ordinarily see, hear, and touch. Fantasy is appealing because it gives shape and form to our strong intuition that there's more to life than the reality that surrounds us." (Brottman 2003) It doesn't matter which world within the film is more important, the land of the Faun or the occupied home. Both are equally "meaningful in how they embody the difficulties, limits, and struggles of human understanding." (Brottman 2003) The question that arises with all of these films isn't which story is more important, more relevant. The question is whether the audience would have connected with the story in the same manner had the film been without its fantastical setting. Would presenting the story without that "mirrored" reality have touched audiences in the same way? Would it have resonated as deeply without that foil, without embracing allegory and archetypes to tell its story? I believe the answer to be a resounding "No".

Paradise: A Thematic Analysis

Stanley Kubrick stated "You don't find reality in your backyard. In fact, sometimes that's the last place you'll find it." (Ciment 2003) With my MFA Thesis Film Paradise, I wanted to make a film that was deeply personal but at the same time entertaining for an audience. As stated previously Paradise is set in the 1600's and features two men who venture deep into the unspoiled American wilderness to search out the mythical fountain of youth, with hopes of saving the dying colony. However, once they discover the magical body of water they find themselves unwilling to leave it, afraid that the water's power will fail unless they stay close. The two find themselves paralyzed by fear and are unwilling to part. Burdened by feelings of guilt and a depreciating bond, they slowly turn on each other.

As a filmmaker, I have two primary duties; the first being I have to create a work that satisfies my own artistic desires, and the second is that I present the audience with an experience that warrants they sit in a darkened room for an extended period of time staring up at a screen. The filmmaker owes the audience an experience that is worthy of this commitment. Telling personal stories under the guise of much larger, entertaining fantasies is a fantastic way of accommodating these two responsibilities; duties that oftentimes come into conflict with each other.

The aforementioned films all incorporated overt allegories within their films. Like many successful films, there are always two stories being told, that which is unfolding on the screen, the conflict between the military and the Navi (Avatar) or the racial disharmonies between aliens and natural born citizens (District 9), and that which is being told through subtext and consequently, allegory. Filmmakers are satisfying their own personal need to tell socially and culturally relevant stories that matter to them, while at the same time recounting an entertaining yarn that can resonate with a large audience.

While presented as a fantasy film, Paradise is deeply rooted in one simple moral question: “Do we allow our fear of the unknown to hinder our quality of life?” This is a universal question that has far ranging implications. In a time when the fear of terrorism and religious extremism runs high, we as a society have lost many freedoms whether we immediately recognize it or not, in exchange for security. When do we allow our fears of the unknown hinder our quality of life? Whether audiences of my film recognize this direct connection to our current cultural climate or not doesn't really matter. What matters is that the question is asked and explored within the film in an oblique way. The message is not overly obstructive. It isn't preachy. It presents a conflict and explores it. However it doesn't do it in a literal way but in a theatrical way.

The central protagonist (Daniel) seeks out the mythical fountain of youth for a good reason. He doesn't seek power or fame; he simply wants to save his dying wife. Daniel wants to do the right thing for the right reasons. However, due to a series of unfortunate events he allows himself to be led astray. After the realization that his wife has passed away, Daniel retreats from the world and into a state of stagnation. He allows himself to be manipulated by the antagonist of the story, Zachary. And it is this manipulation, coupled with his own fear of the unknown, which causes Daniel to never leave the fabled water.

Whether the allegory is immediately recognized or not is inconsequential because the story can function on its own. I have presented a question to the audience that has very real and immediate implications. Audiences can choose to embrace the allegory or not. However, I think the inclusion of challenging material makes a stronger picture, and in the world of box office grosses, a strong picture that works on several levels leads to a greater audience and repeat business. Repeat business is what transforms a financially successful project into a triumph.

Plot Devices: Maintaining Audience Interest

The film begins with a cliffhanger, where a lead character is drowned in a small body of water. This leaves the audience in a state of shock as they are immediately immersed in this cinematic world. After the violence of the first scene the audience will be left completely dumbfounded, asking themselves “Why did the character just do that?” “How did the characters come to this point?” and “Will he get away with it?” All of these questions are fantastic, because it means that you’ve got the audience hooked, and if you structure the remainder of your film correctly, you can sustain audience interest for the remainder of the picture. Other films have adopted this philosophy, most notably Bryan Singer’s The Usual Suspects and Christopher Nolan’s Memento.

Since the climax of the film is told within the opening frames of the film, Paradise is largely told through flashbacks. These breaks in time serve several purposes. Most importantly, they provide the audience moments of insight into the motivations of our central characters. As the audience sees our main characters make a decision in the present timeline, they are then taken to the past, where the same characters have an experience that serves as the motivation for their actions in the current timeline. This is not an unproven technique; the entire series of Lost is based upon this very same principal. This plot device serves as yet another way to maintain audience interest, and it allows our characters a depth they otherwise would be without. It’s also an excellent way of condensing time. Since I have a relatively short period of time to tell this story, I want to employ all narrative techniques to make the strongest, most densely layered character piece possible.

Scene Analysis: Strong Versus Weak

As a director I have the final picture locked within my head before I even step foot on set. The movie is alive; it has already been written, filmed, and cut together. You call action once and it all comes apart. Within all film productions, there is a sacrifice on the part of director. Things happen day in and day out. Some of these circumstances cause you to make decisions based on time, locations, actor availability, or the limitations of equipment. The end result is that these series of decisions and compromises somehow make the scene slightly less than you had hoped it would be. There are other instances on set where a director is presented with something, whether it is in the performance, in the lighting, camera movements, blocking, that you had never before realized. A sense of excitement swells inside and you roll with it.

Within Paradise some scenes did not reach their full potential while others met and exceeded expectation. I will analyze two scenes within the film, and compare and contrast their strengths and their weaknesses.

I believe that the second to last scene of my film, where the conflict builds to its climax and we witness our two characters finally fall apart, is the strongest scene of my movie. The scene has clearly defined beats within it, and with every beat there is a shift in the character's relationship, there is a shift in blocking, and there is a shift in the scene's visual strategy. The scene begins with two characters at the water's edge after an undisclosed period of time. Both look horrible, as if afflicted by some terrible illness. They are caked in mud and filth. The entire beginning is told in looks, and through these sneers the audience feels the rising distrust and tension that has befallen these two characters. Merely through a few simple looks we have established both our characters' internal state of mind, and their relationship, which has shifted dramatically from when we last saw them.

As Daniel steps up and begins his reawakening, we leave the camera on Daniel as Zachary watches with greater suspicion. Once again, it isn't what is being said within the film that is important; it is what isn't being said. The great distrust continues to rise. Daniel's exhaustion overtakes him, and it completely comes through the actor's performance. David Abrams, who plays the character of Daniel, was very well attuned to the camera and always able to play with great subtlety. As he goes off and begins speaking to himself, David allows the moment to play out. I felt it was my duty as director to not break the moment with a cut, which would have been very easy and more economical. The moment plays out in real time, and we the audience is in Daniel's head, drawing the same conclusions as he is. The voice of Zachary, the great serpent whispering in his ear, is represented in the shot design where Daniel's face fills the left side of the frame before Zachary bolts up, demanding that they stay.

The conflict, which had before been told through a series of looks and performances, rises tremendously in the following moments. Daniel turns and confronts Zachary for the first time in the entire film, before vowing to leave and rushing out of frame. Zachary tackles Daniel from behind and a struggle ensues. This is the first time within the film where a flashback scene is told through either a static or a smooth shot. The entire scene is filmed handheld to capture the frenetic energy of what is unfolding within the story. The editing style then shifts to match this decline into madness. Jump cuts of the battle bring the audience into the mind of the characters, exposing their psychological state. The diagetic sound is gone, replaced by rising music. The images shift to slow motion. This is the moment that we have been leading to, that ultimate moment of degradation where one character murders the other. The audience is then left with the silence following the struggle. The camera slows as Daniel's breath calms. The audience watches the moments after a crime, when shock overtakes our protagonist. Shot design, editing, and sound reinforce this transformation from violence to calm.

I believe this scene is the strongest because it has definite character shifts within the scene, and each of these shifts is represented not merely by the interactions of our two characters, but by all of the aspects of filmmaking that are at the disposal of the director.

I feel as though one odd thing about the film is that the scenes actually get stronger as the film progresses. The opposite it true for most films. The weakest scene of the film is between Daniel and Faith as they converse by the bed. The lighting is beautiful, and Daniel's performance is very nuanced. However, the scene features two immobile characters within a small space, and there is only so much movement possible to reinforce the conflicts that arise in the dialogue.

With most film scenes, there are several conversations occurring. There is the literal dialogue between characters. Then, blocking and movement is utilized to either reinforce the dialogue, or it is contradictory to the dialogue revealing that the actions and motivations of the characters do not necessarily reflect that which is being said. This is probably a little closer to real life, where people do not always say what they mean; it also makes for more interesting cinema. Directors then reinforce the story through the pacing of the scene, shot design, sound, music, color, and editing. A director possesses all of these tools within his or her arsenal to develop a scene and to explore the conflicts of the scene.

With this particular moment, as Daniel sits near the bedside, we have so little movement within the scene that I feel as though we lost opportunities by not having more movement. We did not take advantage of the emotional impact of the scene, and I did not actively search for different ways to explore the tension and the relationship between these two lovers in a more satisfying.

I do not think that the scene is a failure by any means. The Director of Photography's lighting within the scene is magnificent. However, I fear we missed opportunities to take these characters places that we had not previously considered. We lost this by merely trying to merely photograph the scene and not actively pursuing ways to make the scene more dynamic.

Conclusion

Filmmakers are faced with multiple responsibilities when telling a story. They must consider their audience and provide the filmgoers with an experience that is worthy of their time. They have to create a film that will resonate with audiences on multiple levels in order to create a film that can be sold to a large portion of the population. Filmmakers must also present subjects and thematic material that is challenging to its audience.

Strong films that stand the test of time explore social and cultural issues that somehow break into the public's consciousness. Oftentimes these two duties come into conflict with each other. However, an excellent way to provide challenging and relevant thematic issues within films is to do so in the form of allegories. Many recent films have employed allegories to tell personal stories and socially challenging material, however they veil the messages within these films so that the audience does not feel as though they are being "preached" to. Such films have been referenced within the course of this discussion, and compared to similar films with the same thematic material but told in a radically different manner. In every case analyzed, the box office consistently favored films that presented their message through the use of an allegory rather than without.

This study is important to filmmakers because it introduces directors and producers to different ways to simultaneously tell the stories they want to make, while at the same time producing financially viable pictures that can perform at the box office. It was this interest in allegories and archetypes that led me to construct my MFA Thesis Film, Paradise. Paradise is a fantastic tale focused on the fountain of youth, and yet the film intends to explore a disturbing cultural phenomenon.

Fantasy allows storytellers this capability. For it is through fantasy, through offering our audiences a reflection of their own world through a fantastic setting that they can more easily and comfortably indulge in the lessons filmmakers explore within their pictures. For "however circumscribed their scope or cliched their language, fantasies are meaningful in how they embody the difficulties, limits, and the struggles of human understanding." (Brottman 2003) And it is through our understanding of the fantasy and its limitless capabilities to tell stories of any form, that we as storytellers can continue to tell the tales we feel must shared with the world.

Works Cited

Alworth, Jeff. "The Dark Knight: Art in the Age of George W. Bush." Blue Oregon (2008): http://www.blueoregon.com/2008/07/the-dark-night/ (accessed May 12th, 2010).

Box Office Mojo. "Avatar." http://boxofficemojo.com/movies/?id=avatar.htm.

Box Office Mojo. "Blood Diamond." http://boxofficemojo.com/movies/?id=blooddiamond.htm.

Box Office Mojo. "Dances With Wolves." http://boxofficemojo.com/movies/?id=danceswithwolves.htm.

Box Office Mojo. "District 9." http://boxofficemojo.com/movies/?id=district9.htm.

Box Office Mojo. "Dr. Strangelove Or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb." http://boxofficemojo.com/movies/?id=drstrangelove.htm.

Box Office Mojo. "The Dark Knight". http://boxofficemojo.com/movies/?id=darkknight.htm.

Box Office Mojo. "The New World." http://boxofficemojo.com/movies/?id=newworld.htm.

Box Office Mojo. "Pan's Labyrinth." http://boxofficemojo.com/movies/?id=panslabyrinth.htm.

Box Office Mojo. "Titanic." http://boxofficemojo.com/movies/?id=titanic.htm.

Briley, Ron. "The Dark Knight: An Allegory of American in the Age of Bush?" George Mason's University's History News Network (2008): http://hnn.us/articles/53504.html (Accessed April 29th, 2010).

Brottman, Mikita. "Allegory and Enigma: Fantasy's Enduring Appeal". Chronicle of HIgh Education (2001): http://www.mikitabrottman.com/articles/enigma.html (accessed May 12th, 2010).

Ciment, Michael. Kubrick: The Definitive Edition. New York: Faber and Faber, 2003.

Corliss, Richard. "Corliss Appraises Avatar: A World of Wonder." Time Magazine (2009). http://www.time.com/time/arts/article/0,8599,1947438,00.html.

Due, Tananarive. "Allegorical Landmines: Aliens and Race in District 9." The Defenders Online (2009): http://www.thedefendersonline.com/2009/08/31/allegorical-landmines-aliens-race-in-district-9/.

Ebert, Roger. "Dr. Strangelove Or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb." The Chicago Sun-Times (1994): http://rogerebert.suntimes.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/19941028/REVIEWS/410280302/1023 (Accessed May 5th, 2010).

Eddlem, Thomas. "Avatar: A Visually Stunning and Perfect Historical Allegory." The New American (2009): http://www.thenewamerican.com/index.php/reviews/movies/2599-avalon-a-visually-stunning-and-perfect-historical-allegory.

French, Phillip. "Pan's Labyrinth." The Guardian (2006): http://www.guardian.co.uk/film/2006/nov/26/sciencefictionandfantasy.thriller.

Internet Movie Database. "Avatar." http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0499549/.

Internet Movie Database. "Dr. Strangelove." http://www.imdb.com/title/tt1136608/.

Internet Movie Database. "Pan's Labyrinth." http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0457430/.

Itzkoff, Dave. "A Young Director Brings a Spaceship and a Metaphor in for a Landing." The New York Times (2009): http://www.nytimes.com/2009/08/06/movies/06district.html (Accessed May 15th, 2010).

Levy, Emmanuel. "Pan's Labyrinth." Emmanuel Levy (2006): http://www.emanuellevy.com/search/details.cfm?id=2571.

Orenstein, Susan. "Achieving Grace: Allegory and The Dark Knight." Film in American Popular Culture (2008): http://www.americanpopularculture.com/archive/film/knight.htm (Accessed May 9th, 2010).

Regl, Robert. "Avatar: An Allegory." OpEd News (2009): http://www.opednews.com/Diary/AVATAR--An-allegory-by-Robert-R-Regl-091231-451.html.

Rollo, Sarah. "Cameron: Avatar Comments on Iraq War." Avatar Movie Fan (2009): http://www.avatarmoviefan.com/movies/reporter-director-james-cameron/.

Rotten Tomatoes: "Avatar". http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/avatar/.

Rotten Tomatoes: "District 9." http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/district_9/.

Rotten Tomatoes: "Dr. Strangelove Or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb." http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/dr_strangelove/.

Rotten Tomatoes. "The Dark Knight." http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/the_dark_knight/.

Rotten Tomatoes. "Pan's Labyrinth." http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/pans_labyrinth/.

Scott, A.O. "A Harsh Hello for Visitors from Space." The New York Times (2009): http://movies.nytimes.com/2009/08/14/movies/14district.html.

Sexton, Timothy. "Hollywood History: Dr. Strangelove." Associated Content (2006): http://www.associatedcontent.com/article/108339/hollywood_history_dr_strangelove.html?cat=40 (Accessed May 15th, 2010).

Siano, Brian. "A Commentary on Dr. Strangelove." The Kubrick Site (1995): http://www.visual-memory.co.uk/amk/doc/0017.html (Accessed May 5rh, 2010).

Stanley Kubrick: A Life in Pictures. DVD. Directed by Jan Harlan. Warner Brothers Studios, 2001.